My friends, Billy and Akaisha Kaderli, lived a normal life… until the day they decided not to.

Billy worked as an investment broker.

Akaisha ran their restaurant.

But they weren’t happy with their daily grind, so they transitioned into a life that was way outside the box.

At 38 years old, the couple sold everything they owned, including their home and restaurant.

They put all of their proceeds ($500,000 USD) into an S&P 500 index fund and decided to retire.

That was 32 years ago.

The couple moved to Mexico and has since spent time in several low-cost countries.

For years, their portfolio was their only source of income.

I wanted to see what would have happened if the Kaderlis had consistently withdrawn an inflation-adjusted 4 percent annually from their initial $500,000 portfolio.

The so-called 4 percent rule was back-tested to 1926.

It suggests that if someone has a diversified portfolio of index funds, they should be able to withdraw an inflation-adjusted 4 percent per year, and the money should last at least 30 years.

Some people say, “the 4 percent rule no longer works” as if they can see the future (Newsflash: nobody can).

Statistically, however, the biggest risk of the 4 percent rule is dying with too much money, as Billy and Akaisha might.

That doesn’t mean you can’t run out of money if the markets fall harder than they have ever done before, over the next several years.

But if you are smart and flexible (which I’ll explain) your money should last forever.

First, let’s look at how the traditional 4 percent rule works, using Billy and Akaisha as an example.

In 1991, they retired with $500,000.

In the first year of their retirement, they would have withdrawn $20,613.

That included an adjustment for inflation, which was 3.06 percent that year.

The following year, 1992, inflation was 2.90 percent.

That year, they would have withdrawn $21,211.

Each year that followed, they would have withdrawn more money to match the rising cost of living.

By March 2023, they would have made 32 annual withdrawals, totalling $976,533.

And their portfolio would be worth $6,496,209.

Yes, that’s $6.49 million.

The S&P 500, however, might have been the world’s best-performing index over those 32 years.

Nobody would have known that would happen, for sure.

Likewise, nobody knows what the best-performing market will be over the next 30 years.

That’s why it’s important to own a globally diversified portfolio of stock and bond market indexes.

As shown below, if the Kaderlis had a portfolio representing 35 percent US stocks, 25 percent international stocks and 40 percent US bonds, they could have still withdrawn $976,533 from their initial $500,000.

And by March 2023, they would have had four times more money than they did when they first retired, 32 years ago.

The 4% rule in action

January 1991 - March 2023

Starting value: $500,000

| Year | Inflation | Withdrawal | Year-end value: S&P 500 |

Year-end value: Globally Diversified Portfolio (35% U.S. Stocks, 25% International Stocks, 40% U.S. Bonds) |

| 1991 | 3.06% | -$20,613 | $630,495 |

$578,417 |

| 1992 | 2.90% | -$21,211 | $656,087 |

$570,779 |

| 1993 | 2.75% | -$21,794 | $699,196 |

$635,017 |

| 1994 | 2.67% | -$22,377 | $685,042 |

$621,012 |

| 1995 | 2.54% | -$22,945 | $918,616 |

$727,195 |

| 1996 | 3.32% | -$23,707 | $1,105,061 |

$775,766 |

| 1997 | 1.70% | -$24,111 | $1,447,724 |

$863,612 |

| 1998 | 1.61% | -$24,499 | $1,837,521 |

$972,764 |

| 1999 | 2.68% | -$25,157 | $2,199,501 |

$1,098,489 |

| 2000 | 3.39% | -$26,009 | $1,974,302 |

$1,038,998 |

| 2001 | 1.55% | -$26,413 | $1,710,516 |

$955,385 |

| 2002 | 2.38% | -$27,040 | $1,304,680 |

$853,790 |

| 2003 | 1.88% | -$27,549 | $1,648,991 |

$1,019,608 |

| 2004 | 3.26% | -$28,445 | $1,797,650 |

$1,106,222 |

| 2005 | 3.42% | -$29,417 | $1,854,061 |

$1,153,623 |

| 2006 | 2.54% | -$30,164 | $2,113,902 |

$1,282,608 |

| 2007 | 4.08% | -$31,396 | $2,196,376 |

$1,361,138 |

| 2008 | 0.09% | -$31,424 | $1,351,838 |

$1,030,707 |

| 2009 | 2.72% | -$32,279 | $1,677,601 |

$1,221,060 |

| 2010 | 1.50% | -$32,762 | $1,895,031 |

$1,326,658 |

| 2011 | 2.96% | -$33,733 | $1,898,555 |

$1,289,188 |

| 2012 | 1.74% | -$34,320 | $2,164,676 |

$1,407,545 |

| 2013 | 1.50% | -$34,835 | $2,826,336 |

$1,577,207 |

| 2014 | 0.76% | -$35,099 | $3,173,033 |

$1,630,334 |

| 2015 |

0.73% |

-$35,355 | $3,177,288 |

$1,580,752 |

| 2016 | 2.07% | -$36,088 | $3,516,659 |

$1,648,201 |

| 2017 | 2.11% | -$36,850 | $4,241,788 |

$1,868,145 |

| 2018 | 1.91% | -$37,554 |

$3,940,822 |

$1,737,328 |

| 2019 | 2.29% | -$38,412 | $5,137,331 | $2,042,677 |

| 2020 | 1.36% | -$38,935 | $6,036,226 | $2,253,792 |

| 2021 | 7.04% | -$41,675 | $7,717,267 | $2,470,227 |

| 2022 | 6.45% | -$44,365 | $6,266,546 | $2,038,639 |

| 2023* | $6,496,209 | $2,089,211 | ||

| Total initial value |

Total withdrawn |

Account value, March 1, 2023 |

Account value, March 1, 2023 |

|

| $500,000 | $976,533 | $6,496,209 | $2,089,211 |

Source: Portfoliovisualizer.com

Pre-tax returns

*To March 1, 2023

When seeing these results, you might wonder why anyone would withdraw just four percent per year.

Prudence, however, is key.

Billy and Akaisha retired at the beginning of a nine-year stock market surge.

Inflation was also relatively low.

Such inflation rates meant they didn’t have to withdraw a lot more money every year to cover the rising cost of living.

Someone retiring in 1973 would have faced a much more challenging time.

U.S. stocks fell 18.18 percent.

The following year (1974) they fell another 27.8 percent.

That two-year drop made 2008/2009 and 2022 look like small dips in the road.

For example, $10,000 in U.S. stocks on January 2008 dropped to $8,103 by December 31, 2009.

But $10,000 invested on January 1973 would have cratered to just $5,906 by December 31, 1974.

Inflation also ran like a world-class sprinter on drugs.

In 1974, inflation was 12.34 percent.

In 1979, it was 13.29 percent. In 1980, inflation hit 12.52 percent.

However, 30 years after withdrawing an inflation-adjusted 4 percent, the investor in a globally diversified portfolio of index funds would have still had more money than when they first retired.

So you might still be asking, “Why not withdraw more than an inflation–adjusted 4 percent?”

Here’s why you shouldn’t.

If global stocks plunge when you first retire and, ten years later, barely gain ground, withdrawing more than an inflation-adjusted 4 percent could get you into trouble.

For example, if someone retired in January 2000 and withdrew more than an inflation-adjusted 4 percent per year, they might be puckering now.

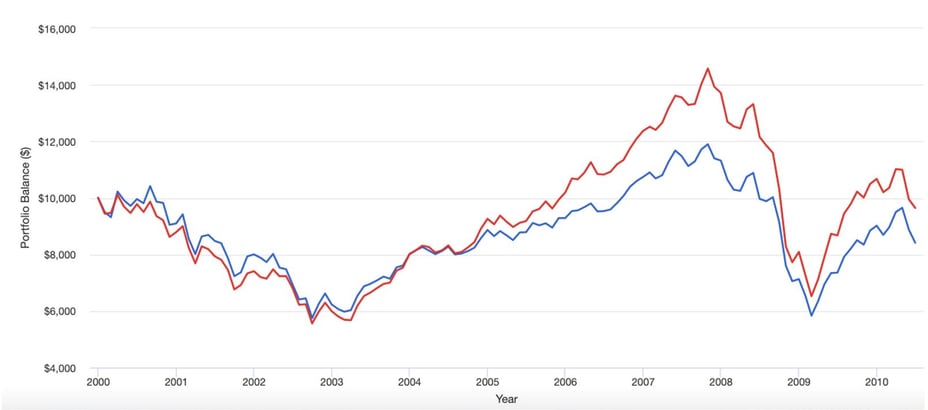

Below, you can see the ten-year performance for US and global stocks from January 2000 to June 30, 2010.

For a decade, stocks went nowhere.

January 2000 to June 30, 2010

US Stocks

Global Stocks

Source: portfoliovisualizer.com

Despite, however, that horrible beginning to the retirement party, if someone retired in January 2000 and withdrew an inflation-adjusted 4 percent per year, they would have withdrawn $612,250 after 23 years.

If their money were invested entirely in the S&P 500, they would have $257,355 remaining by March 1, 2023.

In contrast, if they had a globally diversified portfolio of index funds representing (as with the previous example) 35 percent US stocks, 25 percent international stocks and 40 percent US bonds, they would have $503,695 remaining by March 1, 2023.

Diversification helps a lot. Below, I’ve shown the running portfolio values, as well as the rates of inflation and the annual withdrawals.

As you can see from the S&P 500 column, it isn’t a good idea to fall in love with a single market.

It’s hard to imagine someone retiring in 2000, putting everything in the S&P 500, withdrawing an inflation-adjusted 4 percent per year, and then keeping their cool as their retirement proceeds plunged from $500,000 to $262,007 after just three years.

In contrast, the more diversified investor would have slept a lot better.

The 4% rule faces a horrible time to retire

January 2000 - March 2023

Starting value: $500,000

| Year | Inflation | Withdrawal | Year-end value: S&P 500 |

Year-end value: Globally Diversified Portfolio (35% U.S. Stocks, 25% International Stocks, 40% U.S. Bonds) |

| 2000 | 3.39% |

-$20,677 |

$426,450 |

$469,362 |

| 2001 | 1.55% |

-$20,998 |

$358,688 |

$420,872 |

| 2002 | 2.38% |

-$21,497 |

$262,007 |

$376,449 |

| 2003 | 1.88% |

-$21,901 |

$322,255 |

$437,388 |

| 2004 | 3.26% |

-$22,614 |

$339,973 |

$462,672 |

| 2005 | 3.42% |

-$23,387 |

$336,918 |

$471,262 |

| 2006 | 2.54% |

-$23,981 |

$365,197 |

$510,161 |

| 2007 | 4.08% |

-$24,960 |

$360,285 |

$535,165 |

| 2008 | 0.09% |

-$24,983 |

$201,861 |

$410,318 |

| 2009 | 2.72% | -$25,662 | $234,129 |

$460,763 |

| 2010 | 1.50% |

-$26,046 |

$248,104 |

$488,638 |

| 2011 | 2.96% |

-$26,818 |

$223,673 |

$464,808 |

| 2012 | 1.74% |

-$27,285 |

$232,742 |

$490,017 |

| 2013 | 1.50% |

-$27,694 |

$282,666 |

$531,899 |

| 2014 | 0.76% |

-$27,904 |

$289,895 |

$530,684 |

| 2015 |

0.73% |

-$28,108 |

$262,633 |

$500,503 |

| 2016 | 2.07% |

-$28,691 |

$266,859 |

$501,963 |

| 2017 | 2.11% |

-$29,296 |

$293,741 |

$547,205 |

| 2018 | 1.91% |

-$29,855 |

$248,447 |

$489,720 |

| 2019 | 2.29% |

-$30,538 |

$294,055 |

$550,272 |

| 2020 | 1.36% |

-$30,954 |

$324,470 |

$592,937 |

| 2021 | 7.04% |

-$33,132 |

$374,364 |

$620,246 |

| 2022 | 6.45% |

-$35,270 |

$265,709 |

$491,641 |

| 2023* |

$277,355 |

$503,695 |

||

|

Total |

Total withdrawn |

Account value, March 1, 2023 |

Account value, March 1, 2023 |

|

| $500,000 | $612,250 |

$277,355 |

$503,695 |

Source: Portfoliovisualizer.com

Pre-tax returns

*To March 1, 2023

But let’s address the importance of flexibility with the so-called 4 percent rule. If returns of the future are worse than the past, and if inflation runs wild, retirees might want to make some adjustments.

To increase the odds of their money lasting 30 years, they could avoid giving themselves inflation-adjusted raises during years when the markets drop.

To increase the odds further, retirees could even withdraw slightly less during years when the markets drop.

Assume someone is scheduled to withdraw $30,000.

If the markets drop, the investor could choose to withdraw ten percent less.

In this case, that would be $27,000, instead of $30,000.

But as with the case of Billy and Akaisha, the biggest risk of the 4 percent rule is dying with too much money.

To prevent that, investors could withdraw more than their scheduled amount if the portfolio has several really strong years.

Here’s what Billy and Akaisha’s portfolio looked like during the first few years of their retirement.

When markets soar for several years, skim more off the top

| Year | Inflation | Withdrawal | Year-end value: S&P 500 |

| 1991 | 3.06% | -$20,613 | $630,495 |

| 1992 | 2.90% | -$21,211 | $656,087 |

| 1993 | 2.75% | -$21,794 | $699,196 |

| 1994 | 2.67% | -$22,377 | $685,042 |

| 1995 | 2.54% | -$22,945 | $918,616 |

Notice that despite their withdrawals, their portfolio invested in the S&P 500 index soared to $918,616 by 1995.

Billy and Akaisha were scheduled to withdraw $22,945.

That represented just 2.49 percent of their portfolio’s value.

At that point, they could have re-assessed.

If, instead of withdrawing $22,945 in 1995, they could have decided to withdraw 4 percent of their portfolio’s value: $918,616.

That would have given them $36,744 to spend that year.

The following year, they could have withdrawn more than $36,744, to match the year’s inflation rate.

And if, after several years, their portfolio continues to rise like crazy, they could re-assess once again, to rinse and repeat.

Forget about anyone who says, the “4 percent rule won’t work in the future.”

Forget about anyone who tries giving you a new, sustainable withdrawal rate, like 3 percent or less.

Such people are assuming they can see the future.

And nobody can, of course.

Regardless of what happens, flexibility is key.

Use the 4 percent rule as a base, and operate from there.

Andrew Hallam is the best-selling author of Millionaire Expat (3rd edition), Balance, and Millionaire Teacher.