[Estimated time to read: 4 minutes]

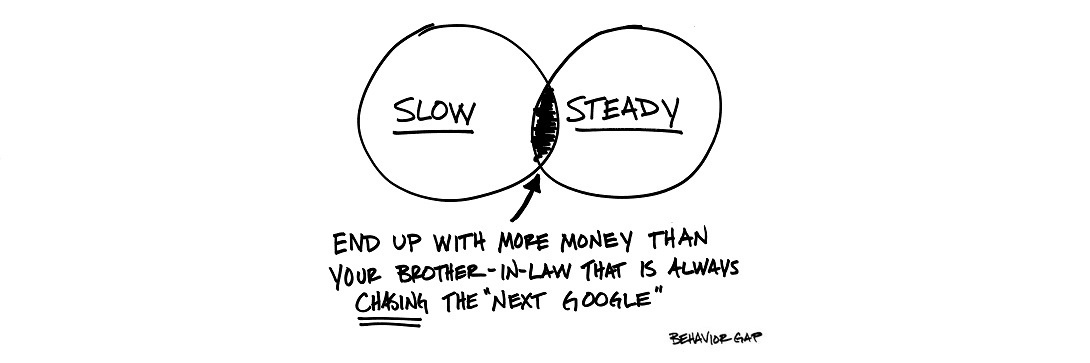

Investors are suckers for recent winners.

![]()

We read in the newspaper that such and such a sector or geographical region is on a good run, and we instinctively want a slice of the action.

Of course, the fund industry is acutely aware of this natural human tendency, which explains the emphasis in its PR and advertising on who and what’s done well over the last few years, or even the last few months.

But, from an investment point of view, chasing what’s hot is not a good idea.

Take asset classes, for example.

Just because a particular type of asset has outperformed, say, for two or three years, that doesn’t mean that it’ll continue to do so into the future.

On the contrary, it often means that it’s due for some sort of correction.

Fund performance is exactly the same.

It comes back to evidence

By the law of averages you would expect a reasonable number of actively managed funds to outperform for short periods, but only a tiny proportion of them succeed in beating their benchmarks over more significant periods of time.

In January 2016, Morningstar published a paper called Performance Persistence Among US Mutual Funds.

Researchers analysed fund performance across 14 different categories and over a range of time periods.

The study found that:

- over the long term, there is no meaningful relationship between past and future fund performance;

- although there is some evidence that relative fund performance persists in the short-term, this appears to be attributable to greater exposure to momentum stocks (the idea that if a stock has done well the likelihood is that it will continue to do so - a notion usually discounted by evidence-based firms) rather than superior manager skill; and

- in most cases, the odds of picking a future long-term winner from the top-performing quintile in each category aren’t materially different than selecting from the bottom quintile.

In conclusion, the research team said this:

“It is difficult to identify funds that will outperform over the long term based solely on their past performance. The difference in success rates between the top and bottom prior performance quintiles is fairly small in most categories in holding periods longer than a year.”

If you sold funds for a living...

Now, imagine three funds — A, B and C.

Over the last three years, Fund A has produced stellar returns, Fund B’s performance has been mediocre and Fund C has underperformed.

Which fund are investors most likely to want to invest in?

Of course, Fund A.

Now ask yourself, if you sold funds for a living, say you worked for a fund shop or a brokerage firm, which fund would you find easier to sell?

If you were a journalist writing about the different funds available, which fund’s manager would you choose to feature in your article?

If you edited an investment magazine or a slot on a financial TV channel, and you needed some expert analysis, which manager would you ask?

Again, it’s obvious.

Fund A wins every time.

The underdog wins...

The next question to consider is this: Which fund — A, B or C — is likeliest to outperform in the future?

According to another recent study of equity fund performance, the answer is in fact Fund C — i.e. the fund that’s underperformed for the last three years.

The next best returns are likely to come from Fund B, the one with a mediocre recent track record.

Counter-intuitive though this might seem, it’s Fund A — the hot fund that everyone’s talking about — that is likely to deliver the lowest returns in the future.

So, what are the implications of studies such as these for investors?

There are three important ones.

1. First, don’t assume that short-term outperformance is down to skill.

It’s far more likely to be a function of investment style or simply random chance than a manager’s talent or expertise.

Skill, in theory, is repeatable, but luck isn’t, and it’s in the nature of investment style that what works well for a period will eventually stop doing so — hence the prevalence of mean reversion, which veteran indexing advocate Jack Bogle once described as “the iron rule of financial markets”.

2. Secondly, it really isn’t wise for investors to select a fund on the basis of past performance, particularly short-term performance.

If you really, really insist on including an active fund or two in your portfolio, you’re probably better off selecting a recent loser than a recent winner.

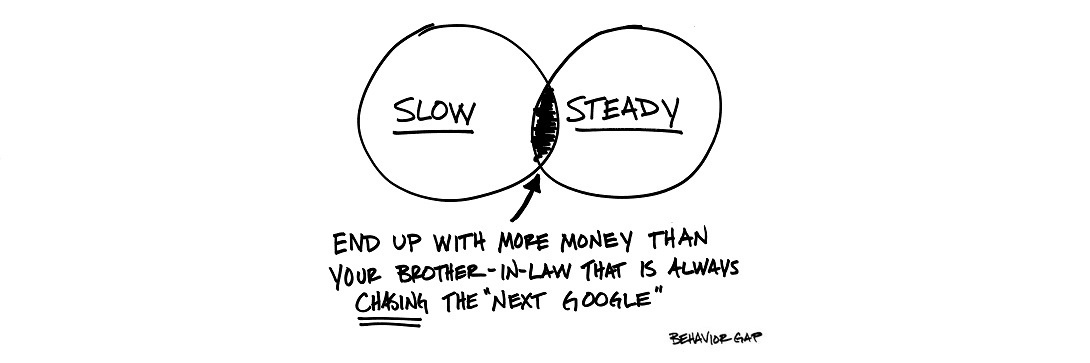

3. Thirdly, investors need to resist any temptation from the fund industry or the media to focus on the short term, and should set their sights instead on the very long term.

A 25-year old today might not retire for another 45 or 50 years, or even longer.

In that context, a marginal outperformance over the next 12 months means nothing at all.

The simplest and most efficient way to invest for the long term is to buy a globally diversified portfolio of low-cost index funds and, apart from occasional rebalancing, to leave it well alone.

To quote the investment author Larry Swedroe,

“the prudent strategy for investors is to act like a postage stamp. The lowly postage stamp does only one thing, but it does it exceedingly well — it adheres to its letter until it reaches its destination.”

For more information on active vs passive investing, download our eBook.