The S&P 500 is an index of 500 US stocks that covers roughly 80 percent of the available US market capitalisation.

It’s one of the oldest and best-known stock indexes in the world, with its companies holding $7.1 trillion in assets. That’s $7.1 trillion US dollars invested in index funds that are tracking the S&P 500 index.

That's a lot of money.

The index serves as a barometer for the U.S. stock market and economic health, often reflecting investor sentiment.

Current performance

The index had a bumpy 2022, ending the year down 18%, its worst performance since 2008. But now, despite dealing with tight monetary conditions and an unexpected banking crisis, it’s currently entering a bull market after the longest downturn in decades.

The 5 biggest companies by sector and weight, as of today, are:

| Company | Symbol | Sector | Weight (%) |

| Apple Inc | AAPL | Info Tech | 7.02% |

| Microsoft | MSFT | Info Tech | 6.42% |

| Amazon.com Inc | AMZN | Consumer Discretionary | 3.30% |

| Nvidia Corp | NVDA | Info Tech | 2.80% |

| Alphabet Inc Class A | GOOGL | Communication Services | 2.06% |

Over the last decade, big tech names have dominated the index.

The tech sector makes up over 26%, with Apple, Microsoft, and Nvidia as the top S&P 500 companies by market capitalisation.

(In fact, Nvidia alone is worth nearly as much as the entire real estate sector.)

Amazon is the third-largest company in the index.

While shares tumbled in 2022 amid slowing sales, they have since rebounded by about 46% this year. Like Amazon, consumer discretionary firm Tesla has also seen a strong reversal as the index’s 10th biggest stock by weight.

In the financial sector, Berkshire Hathaway has the highest weight (1.7%) while UnitedHealth Group (1.3%) is the top in health care. This health conglomerate even towers above JP Morgan Chase, the biggest bank in America.

In terms of sectors, information technology, health care, and financials have the highest share in the S&P 500. Together, they cover over half the index.

On the other side of the S&P 500, the financial sector was rocked by sudden collapses.

Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Financial Group shares lost the most ground in the first quarter, after both banks collapsed, shedding nearly all of their value in a matter of 30 days. In fact, when looking at the first 3 months of the year, 7 of the 10 worst performers on the index were banks or financial companies.

There are two major themes playing out this year so far.

First is that seven big tech companies—Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Google, Tesla, Meta, and Amazon—are driving virtually all of the index’s gains. These companies have seen double or triple-digit returns this year so far.

Secondly, the energy and healthcare sectors have seen the highest outflows, at $9 billion and $4 billion, respectively.

Is it a good idea to invest in the S&P 500?

To answer this, I want to highlight 3 things. I also cover these in my video, below:

1. Investing in the S&P 500 has worked out really, really well

The average annual return of the index was 10% from 1980-2022, excluding dividends. Of course, there are some companies that deliver much higher returns in any given year.

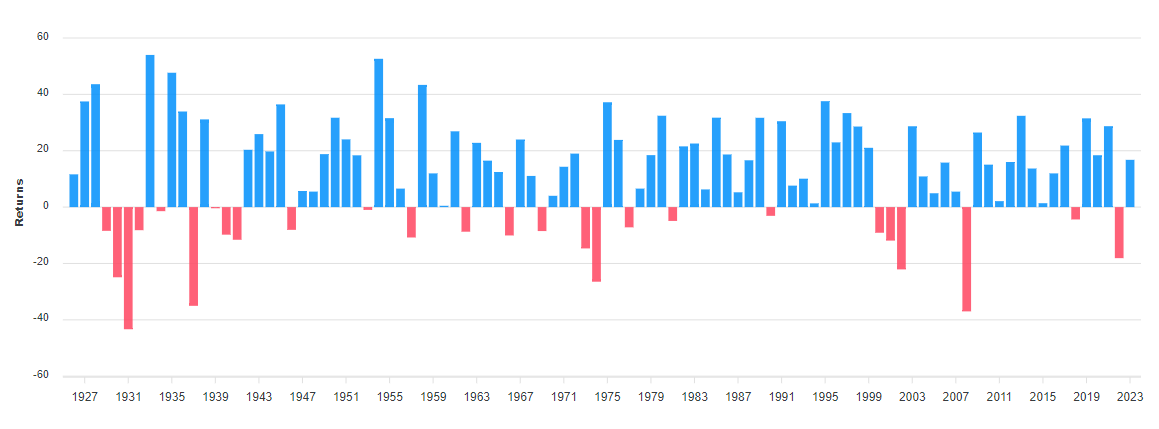

Since it began in 1957, it’s gained about 10.7% on average annually (any returns before this time have been hypothesised by academics):

S&P 500 total returns

The index has done slightly better than that in the past decade, returning about 14.7% annually.

The S&P 500 is synonymous with index investing.

Lots of people refer to themselves as ‘index investors’ while only investing in the S&P 500. One of the most compelling arguments for investing in the S&P 500 is its past performance.

The risk-adjusted performance, especially since the end of the financial crisis, has been staggering.

A few years ago, a method called bootstrapping was used to examine the performance of the S&P 500 from 2009 – 2018. It showed that statistically, the actual performance of the S&P 500 over that time was almost too good to have been statistically possible.

The simulation took all the historical monthly returns for the S&P 500 from 1926 to October 2018, then drew out 116 monthly returns to create a return series that is the same length as the period from March 2009 to October 2018.

This can be done countless times to simulate possible outcomes using the actual historical data as a sample set. The analysis ran 100,000 simulated 116-month periods, which was then compared to the actual performance of the S&P 500 index.

The findings were unbelievable.

Of the 100,000 bootstrap samples, only 0.57% of them had better risk-adjusted returns than what the S&P 500 actually achieved, in the nine-year period.

Remember though, past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

In fact, the term "the lost decade" refers to the ten-year period from 31st December 1999 through to 31 December 2009, when the S&P generated an annual return of -0.9% over the period. This was the second decade where this had happened. It's therefore entirely possible that the last 13 years is simply a return to the mean average and the next decade may well be far more average.

Human nature always means retail investors tend to buy what is 'hot.' Typically this is right before it gets cold.

2. The S&P 500 is a lot more actively managed than most people realise

It’s not simply the 500 largest stocks in the US. It’s a committee-based index. The stocks that go into the index are selected by a committee of people, not by an algorithm.

There are selection criteria, but the ultimate decision on inclusion and exclusion for the index is made by humans. The goal of this committee is to build an index that represents large-cap US equity markets, but there's still a human element, which makes repeating the exceptional past results of the index even more unlikely.

3. There are 3,500 stocks in the US market

I mentioned that the S&P 500 covers roughly 80% of the US stock market capitalisation.

That's pretty good coverage, but there are close to 3,500 stocks that actually exist.

By owning only 500 of these 3,500, you’re missing out on accessing the full potential of the US stock market. There are also many more thousands of excellent stocks that exist globally.

It's true, a small number of stocks have driven most of the wealth creation in the US and global markets over time.

Also, smaller stocks, including many of the roughly 3000 stocks that are not in the S&P 500, tend to beat larger stocks over the long term.

Again, while the S&P 500 has recently been able to beat the wider US and the global market, the likelihood of that performance persisting is low.

Well-informed investors know finding winning stocks is like finding a needle in a haystack, and that giving up diversification can come with a hefty price.

More on diversification

Past performance aside, one of the most common arguments that I hear in favour of investing in the S&P 500 is that its constituents get roughly half of their revenues from outside of the US.

Does this mean there’s no need to diversify globally? No.

The fact that the S&P 500 constituents have global revenue sources does not offer you, the investor, the benefits of global diversification.

A 2019 paper from Vanguard, titled Global Equity Investing, The Benefits of Diversifying and Sizing your Allocation, addressed this exact question. The authors showed that while US stocks had the lowest volatility of any country from 1970 to 2018, the global market cap weighted portfolio, including the US and all other countries, had even lower volatility.

A frequently rebalanced portfolio of low-cost funds invested in the best companies of the world, has statistically proven time and again to return more and have lower volatility than any individual countries.

This is, of course, 'the free lunch of diversification' espoused by Nobel Prize-winning laureate and economist Harry Markowitz at work.

The Vanguard paper goes on to explain that, even though markets may tend to move more in the same direction, the magnitude of those movements has continued to be very different from country to country, meaning that there is still a substantial benefit to owning global stocks.

In 2011, a paper from AQR called International Diversification Works (Eventually), looked at 22 developed markets from 1950 to 2008 and examined the effects of diversification over short and long-term periods.

Of course, anyone investing in stocks should be most concerned about the long term.

The authors found that while short-term market downturns can be driven by investors changing risk preferences or panicking, as some may describe it, longer-term results are driven more by the economic performance of countries.

It says,

"Diversification protects investors against the adverse effects of holding concentrated positions in countries with poor long-term economic performance. Let us not fail to appreciate the benefits of this protection."

Of course, the world can change. The US stock market currently makes up roughly 60% of the global market capitalisation, but that’s not always been the case.

In 1989, Japan made up 45% of the global stock market, while the US was sitting at only 29%. Betting on one country, no matter how dominant its market is, increases the likelihood of a bad outcome and it is generally expected that the US share will reduce in the future with other geographic regions expected to increase.

Finally, a word on valuations

No discussion about investing in the S&P 500 or US stocks in general, is complete without mentioning valuations.

I'm not a market timer, but it’s well-documented that current valuations are the best predictor of future returns.

When prices are high, future returns tend to be lower. The S&P 500 has a price-earnings ratio of 31.4 as of 31 July 2023, which is 55.7% above the modern-era market average of 20.2, putting it 1.4 standard deviations above average. This suggests that the market is overvalued.

Why does this matter?

P/E ratios can only go so high. To justify a P/E ratio that is consistently above its own historic average for long periods of time, the US stock market must not only continue to grow, but would need to continue to grow at a continuously increasing rate.

I'm not saying that you should bet against US stocks. We know that valuations can continue to rise for a long time, but betting only on the most expensive market isn't sensible.

In summary

So, the S&P 500 is probably not the most reliable approach to capturing US stock returns, despite its past performance.

It also doesn't offer exposure to global stock returns, even though its constituents have global revenue sources.

If you’re currently using the S&P 500 for your US equity allocation, that’s OK.

Compared to an actively-managed fund or a stock-picking strategy, the S&P 500 is well-diversified and can be accessed for almost no cost due to the massive scale of the ETFs tracking it.

However, the S&P 500 isn’t the only index you should own in your portfolio, and it probably isn't even the best index to own for your US stock exposure.

As usual, the best bet that most investors can make is to invest in a globally diversified portfolio of low-cost funds in the world’s best companies.