You’ve probably heard of the 4% retirement rule.

It’s considered safe by experts.

But what happens when it’s put to the test against falling markets?

And inflation-adjusted?

In a recent conversation with Andrew Hallam, author of the best-sellers Millionaire Teacher and Millionaire Expat: How To Build Wealth Living Overseas, he spoke about this exact point.

He told me about his friend, a lawyer, who retired 27 years ago, and has since lived by this 4% rule of thumb.

The friend, Bob, lives off the proceeds of his investment portfolio and has more money now than when they first retired.

It might not sound unusual but Bob and his wife, Alice, have been retired for 27 years.

In 1991, they quit their jobs when they were just 38 years old.

In search of greener pastures, they sold their business, their home, and nearly all of their possessions.

They retired decades before conventional wisdom says they should.

The couple put their entire proceeds, about $500,000, in Vanguard’s S&P 500 index fund. "We knew that we were going to be retired for a really long time," says Bob, "so we decided not to include bonds in our portfolio".

The couple planned to spend no more than 4% of their portfolio each year.

To stretch their money, they spend most of their time in affordable countries.

They have since tweaked their investments.

But I wanted to see what would have happened if the couple withdrew an inflation-adjusted 4% annually from their initial $500,000 portfolio.

In 1991, the first year of their retirement, they would have withdrawn $20,613.

That included an adjustment for inflation, which was 3.06% that year.

The following year, 1992, inflation was 2.90%.

That year, they would have withdrawn $21,211.

By the end of 2017, they would have made twenty-seven annual withdrawals, totalling $775,592.

By February 28, 2018, their portfolio would have been worth more than $4.3 million - despite those withdrawals.

This doesn’t include capital gains or dividend taxes.

But one thing is clear: the couple's portfolio would have been worth a lot more than its initial $500,000.

I wanted to see what would have happened if they had built a more diversified portfolio.

I back-tested the following:

- 40% Vanguard Total Bond Market Index

- 35% Vanguard S&P 500 Index

- 25% Vanguard International Stock Market Index

After withdrawing the same $775,592 over twenty-seven years, they would have had more than $1.8 million by February 28, 2018.

The below table is the 4% rule in action between 1991-2018 with a starting value of $500,000.

The biggest risk of withdrawing an inflation-adjusted 4% per year might be dying with too much money.

But that doesn’t mean retirees can’t run out of money.

In 1999, Philip L. Cooley, Carl M. Hubbard and Daniel T. Walz tested the 4% rule back to 1926.

They looked at rolling 30-year retirement periods, publishing their results for the Association for Financial Counseling and Planning Education.

Two things are worth noting.

Based on rolling 30-year retirement periods, a portfolio of 100% stocks had a 98% chance of lasting.

But the portfolio’s survival improved to 100% if it included a 25 to 40% allocation to bonds.

Long-term, stocks easily beat bonds.

But after stocks take a dive, withdrawing an inflation-adjusted 4% can take huge chunks out of the portfolio’s total value.

By including some bonds, retirees might reduce risk.

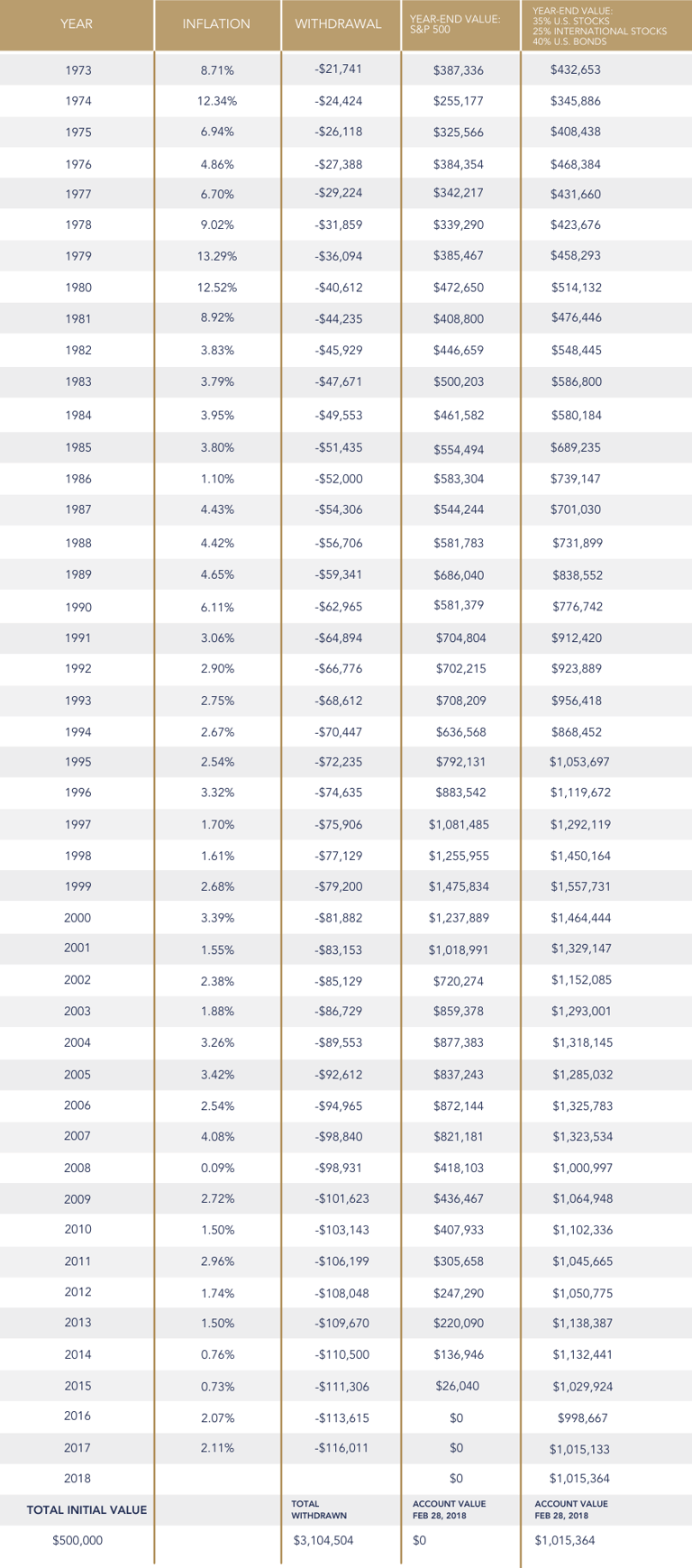

I back-tested two retirement portfolios to 1973.

I chose that year because it would have been one of the most horrific times in history to start inflation-adjusted withdrawals from an investment portfolio.

In 1973, U.S. stocks fell 18.18%.

The following year, they fell another 27.8%.

That two-year drop would have made 2008/2009 look pleasant by comparison.

For example, a $10,000 investment in U.S. stocks on January 2008 would have been worth $8,103 by December 31, 2009.

In contrast, a $10,000 investment on January 1973 would have been worth just $5,906 by December 31, 1974.

If that wasn’t bad enough, inflation started to run like a pack of wild dogs.

- In 1974, inflation was 12.34%

- In 1979, it was 13.29%

- In 1980, inflation hit 12.52%

The below table is the 4% rule in action between 1973-2018 with a starting value of $500,000.

Both portfolios would have served most retirees well.

After 30 years, the portfolio invested entirely in stocks would have been worth: $859,378.

The portfolio allocated 60% stocks and 40% bonds, would have been worth: $1,293,001.

But early retirees (and those that live a long time) might face greater risks if they face falling stocks and run-away inflation.

For example, those that retired in 1973 with 100% stocks would have run out of money by 2015.

The balanced portfolio would have lasted longer.

But even then, it faced a dim future.

As seen in the table above, if an investor continued to withdraw an inflation-adjusted 4% per year, by 2017, they would have withdrawn more than 10% of the portfolio’s remaining value.

Bob and Alice, however, didn’t face falling markets and run-away inflation.

You probably won’t either.

But nobody can see the future.

That’s why investors need to put prudence in their favour.

Keep investment costs low, diversify, and if stocks fall hard or inflation runs wild, try to sell a little less than you originally had planned.

After all, we can’t control the market.

But we can control our costs and our behaviour.

Many thanks to Andrew again for sharing this couple's story.