An interview with Kames Capital High Yield Global Bond manager Claire McGuckin

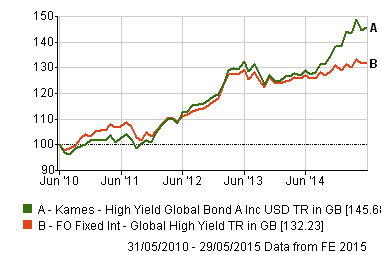

Claire McGuckin is the co-manager of the $400m Kames High Yield Global Bond Fund, with Phil Milburn. The fund, which is available through AES International’s White List, was launched in 2007 and is in the first quartile over one, three and five years.

It has grown by 80% in value since launch and currently pays a quarterly distribution of 4.04%.

Claire joined Kames Capital in 2012 from L&G Investment Management. Here, she talks to Simon Danaher about the fund, her career and why she’s recently bought into Burger King.

What was it that attracted you to Kames to begin with and how have you found your time working with Phil Milburn so far?

CM: There were two main attractions of working for Kames. The first was the very strong track record of the fund, which has been in existence for a long period of time, and had been run very well through different and varied market circumstances.

The second was working with Phil Milburn, David Roberts and the other members of the team. I was very impressed with their general collegiate spirit. The fact is that they are very, very good at what they do, that they know the markets very well, and I felt it was somewhere that would be a pleasant and yet challenging place to work.

What was it that attracted you to the fixed income market originally?

CM: It was a natural career progression. I started out as a credit analyst at NatWest many moons ago. So credit analysis has always been the baseline of what I’ve done in my career. In fact, I was actually sponsored by NatWest to go to university, so I committed to banking quite early on.

When I started, the fixed income market was an attractive and growing part of the asset class and then I gradually moved from job to job and became more embroiled in it.

So what exactly are “high yield bonds” and how do they differ from other bonds?

CM: A bond is effectively a loan to a company from a group of investors, such as ourselves, who will take a proportion of the loan for a fixed term, which could be anything from five, seven or even 10 years at a fixed rate of interest. (Click here to read an explanation of how bonds work).

What differentiates high yield bonds from other bonds is that the companies tend to have slightly higher risk. They tend to have a little bit more debt in their structure and to be higher, what we call ‘leveraged’ – that is: they owe a greater multiple of money in terms of debt versus their income, than investment grade credit. So they’re just slightly riskier.

To help us understand, can you give examples of both an investment grade and a high yield grade bond?

CM: Yes, within the telecoms sector, Vodafone is an investment grade company. It’s a big global company that has a very strong balance sheet. At the other end of the spectrum you have Charter Communications, which is actually at the higher end of high yield space. Again, it’s a global company, but it has more debt on its balance sheet in terms of how it runs the business.

Is it fair to describe high yield as the ‘sexy end of bond investing’ because it arguably needs a bit more skill? Is that what has kept you interested over your career?

CM: It depends. I think my investment grade colleagues would probably not be happy with me if I said that my job requires more skill than theirs.

There are different complexities depending on which end of the spectrum you’re investing in. An investment grade company tends to have more complexity in terms of the rates market. For high yields, the attraction for me is that the credits tend to be more complex and that’s where my base love, if you like, comes from.

It’s the credit analysis, the understanding of the companies, the understanding of what the trajectory of the company is, and whether there’s likely to be a positive outcome from an investment in it which fascinate me.

There have been wobbles in the bond market recently and talk of its bull run coming to an end. Should investors be concerned?

CM: I think there’s little question that we are moving through a period of normalisation, back to a more traditional monetary policy after the very loose monetary policy over the last few years.

It will be a very slow transition back, because it was a very big financial crisis and, while there are certainly expectations that, particularly the US will start to move interest rates sometime soon, we expect that the relevant governing bodies will remain very cautious in how they do that.

From the high yield perspective, it’s slightly easier because the rates market is less of a factor when you’re analysing the high yield bond, as the yield from government rates makes up a bigger proportion of the overall yield that you get. Effectively, an improvement in the economy should be good for high yield companies, which means that you should expect to get paid slightly less for the actual credit risk of the company and therefore net more. We don’t really expect too much of an impact from a normalisation of the monetary policy on high yield bonds on the whole.

Generally speaking, when you’re choosing a bond, what is it that you’re looking for in a company?

CM: What we don’t tend to be attracted to are companies that are what we call ‘deep cyclicals’. This means companies whose earnings can move very quickly in relation to movement, say, in a commodity price, like iron, as an input.

What we’re looking for are companies that have a bit more of a stable profile, and businesses that can adjust and adapt to different market situations or events. We like companies where there’s a nice balance at the end between their expenses and their income. What the normal man in the street would call ‘discretionary spending’ or what we call, from a company’s perspective, ‘free cash flow’.

This tends to mean that we don’t own a lot of chemical companies; we don’t own a lot of steel manufacturers; but we do own a lot of healthcare companies, consumer non-cyclical companies, food manufacturers and the like.

Is there a recent addition to the portfolio you can give as an example?

CM: One most people would probably recognise is Burger King.

Burger King was a subject of a leverage buy some time ago. It also did a big acquisition recently of a Canadian coffee chain. Warren Buffett is involved in the Burger King structure, as well.

Mr Buffett has a lot of reserve money invested in Burger King, so we like the underlying business. We think it’s got a good market position and we thought it was an attractive opportunity with, as we say, a lot of quite serious investors who stand in the background who also believe in the company.

Please talk us through the selection process when you’re making an investment.

CM: We, as the fund managers, are also the analysts within the Kames fund, which can be fairly unusual. Some fund management groups completely separate the two. We think that there’s much greater attachment to the investment when you’re actually formerly involved in it as a as an analyst. I look after healthcare and energy sectors.

We will be presented with an opportunity by one of the banks that will say, for example, ‘Company X wants to raise £500 million for eight years.’ The bank will provide us with a booklet which can be anything from 200 to 600 pages, that gives us the background of the company.

These can contain who they are, what they do, the history in terms of how they’ve performed over the last few years, their market position, how the management wants to run the company, what their expenses are, how they fit within their peer group and competitors, and what the strategy for the company is. All manner of stuff. Effectively, my job is to look for the information that isn’t there.

Based on my experience, it has something to do with making an assessment of the management team and the business (either in that sub-industry or the countries it’s involved in), the legal processes around the country, or the company itself.

The process of being a good credit analyst is really about the information that isn’t there, as much as it is about the information that is.

I would also put together a financial model that would say, ‘Right, over the course of the next few years, based on the history of the company and the trajectory so far, my conversations with the management team and the overall economic environment, I expect the earnings of this company to do X, Y or Z over the next two to three years.’ That would impact the debt of the company and its ability to pay its interest on an annual basis in this way.

We are looking for companies that obviously have a positive trajectory for business and financials, and also a management team that has a clear idea of a strategy and a clear financial set of limitations that they’re willing to operate within to achieve that strategy.

Then, once we’ve decided whether we actually like the company, then we will look at the interest rates that are on offer compared with the market.

Would you ever go back and make any recommendations to the company so they can improve their business, and would you go back and say, ‘We don’t think that you’re offering enough of a return’?

CM: Yes. Absolutely. On all occasions when there’s a new issue, we can feedback to the lead managers. The impact of that feedback from us will vary depending on where we are in the overall market.

What we have been concerned about for the last couple of years, particularly in Europe, is that there has been a lot of money coming in to the asset class. That has meant that other fund managers have needed to invest, whereas we, as a global fund, can look elsewhere.

We are very focussed on investment discipline and not just chasing trends in the market. There are certainly occasions, and there have been occasions, when the market is in a slightly less strong technical state, where in-flows aren’t as dominant, and on those occasions, we have more of an opportunity to shape the structure of the deal.

The important thing is to retain investment discipline and to be willing to walk away from a deal where you do not think the remuneration is appropriate in relation to the underlying credit.

What have been the biggest highlights and biggest challenges of your career so far?

CM: I think the biggest highlight is obviously coming to work for Kames and moving to Edinburgh and working with Phil. Working on such a successful fund has been a very attractive part of the last couple of years.

In terms of challenges, we’ve just gone through quite a significant financial crisis, so I think all of us came out on the other side with slightly more grey hair than when we went in. It’s part and parcel of the job and there will always be ups and downs. Certainly, I think 2008, 2009 and 2011 were probably the most challenging years many people have had in their career.

Are there any investments I’ve made but regretted? Absolutely. You know, if there’s a high yield manager out there that says that they’ve never lost money on something, frankly, they’re lying, or they’re not taking enough risk.

I think one of the things that we emphasise quite clearly is review discipline. It’s easy to buy a bond. It’s much harder to decide to sell a bond when you’ve lost some money on it.

It is that review discipline that remains key to the successful management of a high yield fund.

Not every investment will go the way you want, and a constant revisiting of the basic facts and what’s going on in relation to new headlines and how the market feels about stuff, is essential.

If you are interested in investing in the Kames High Yield Global Bond Fund or would like to find out more about the funds we recommend, click the link below to speak with a member of our investment team.