This retired professor asked his students every year how much money it would take for them to spend a year in prison. Their answer might shock you

I met a new friend this week.

As we rode our bikes in the hills above the French city of Nice, he asked an unusual question,

“If someone offered to pay you a lump sum to spend a year in a minimum security prison, how much money would it take?”

The sixty-six-year-old is a retired college professor who works part-time doing web design.

He asked his students this question every year.

"Did any of them say they wouldn’t go to jail for any amount of money?” I asked.

“Nope,” he replied.

“Everyone had a price.”

How someone responds to that question would likely depend on their age, how much money they have and their current life circumstance.

A person who doesn’t have enough money to eat, for example, might jump to earn a $100,000 lump sum by spending a year in prison.

A wealthy altruist might do it for $1 billion, with the goal of donating it to charity.

My cycling companion said he would spend a year in prison for $1 million.

He and his wife live on the proceeds of his part-time work and their monthly, American Social Security pension payments.

But I wouldn’t do it…for any amount of money.

I thought about a friend.

Her name was Nathi.

She was 35 years old.

She was beautiful, inside and out.

She exercised every day and was in phenomenal shape.

Two weeks ago, we learned that Nathi had an aneurysm while taking a shower.

Her loving husband, Andrés, rushed her to the hospital.

Two days later, she died.

My wife and I loved her.

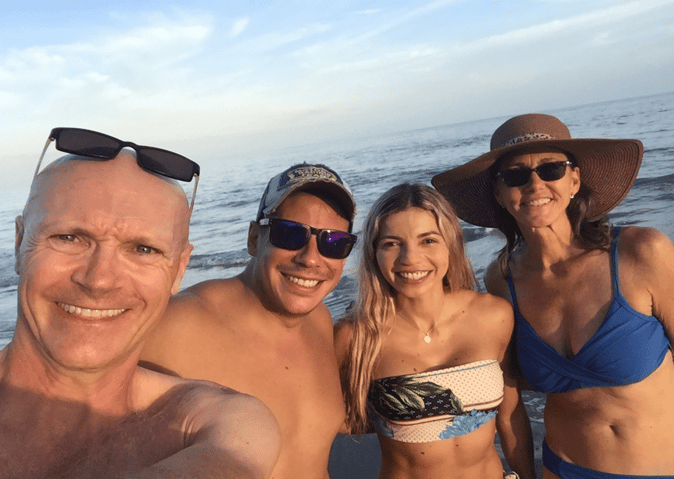

From left to right: Andrew, Andrés, Nathi and Pele

Nobody is really going to offer you, or anyone else, money to spend a year in prison.

But it’s worth discussing what we might do for money…and why.

In my book, Balance, I referenced research indicating that once our basic needs are met, more money only marginally increases our life satisfaction.

If more money continued to boost life satisfaction, the wealthiest people you know would be the happiest.

But we know that isn’t true.

And based on a comprehensive, multiple-country study by Perdue University, life satisfaction and income are eventually, inversely correlated.

For example, people who earn $250,000 a year living in Western Europe or the Middle East report lower levels of life satisfaction, compared to those who earn $115,000 a year.

This doesn’t mean everyone who earns above $250,000 experiences lower life satisfaction than those who earn $115,000 a year.

But on aggregate, that’s the case.

If you’re wondering why the highest-income people aren’t generally as happy, there are several theories.

For starters, they often have higher-pressured jobs.

This can affect their sleep, their time spent relaxing and their daily stress levels.

High-paying jobs also tend to require extensive time commitments.

That often means less time spent with family and friends.

According to Harvard’s eight decade-long study on happiness, the highest correlation with happiness comes from having solid, loving relationships.

Having a time-intensive job can also mean less time for exercise.

Physical activity reduces stress levels, allowing us to sleep better and boost our immune systems.

That’s why I’m a big proponent of balance: choosing a career you love that doesn’t take too much time from life’s more important things.

And if you invest your money effectively, you won’t need to trade as much time for money.

Investing can also provide choices: to take a year off, retire early, or take a lower-paid job you enjoy.

Time, after all, is the only non-renewable resource we have.

And none of us know when that time will run out.

I’m not just referring to how long you will live.

I’m also referring to when the people you love will die.

Nobody knows. There are no guarantees.

This brings me back to Nathi…kind, beautiful Nathi and her wonderful husband, Andrés.

If I had asked them, last month, how much money they would have accepted to spend less time together, I believe they would have laughed and said, “No amount of money.”

And today, there’s no amount of annual income and no lump sum that Andrés wouldn’t give to have more time with Nathi.

When we think of love and pending death, it doesn’t cloud our priorities.

It clarifies them, instead.

Andrew Hallam is the best-selling author of Millionaire Expat (3rd edition), Balance, and Millionaire Teacher.