Indexing is the most thoroughly researched, best-supported method yet devised for ensuring good investing results over the long term.

But don’t just take my word for it.

A long list of Nobel Prize winners and academic researchers – including William F. Sharpe, Eugene Fama, and Burton Malkiel, to name a few – will be happy to tell you about its virtues.

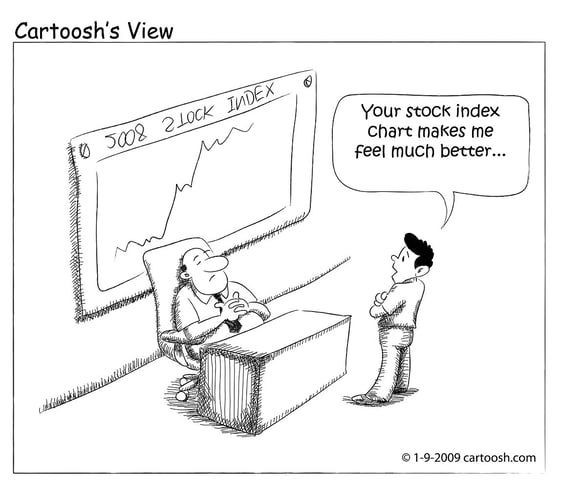

But evidence is one thing and feelings are another.

Index investors still have to deal with their own emotions.

From elation to despair and back again, indexers are just as exposed as anyone else to the market’s surges and swoops.

The stress that goes along with these inevitable highs and lows is the single biggest reason why people sabotage themselves by jumping out of an indexed portfolio at just the wrong time.

Fortunately, you can improve your odds of investing success – not to mention your digestion – by being prepared for the three stages of an index investor’s life.

Let me explain.

THE NOVICE INVESTOR: “I’ve discovered magic”

When the market is going up – as it normally does – index investors should feel quiet satisfaction.

An index fund, by definition, rides along with the market index.

If a given benchmark, like the S&P 500, is on the rise, so are the fortunes of the index investors who are tracking it.

But these natural feelings of satisfaction can get out of whack.

When the market is enjoying a particularly strong, sustained rise – think tech stocks during the 1990s or the S&P 500 in recent years – indexers tend to get carried away.

During these glorious patches, a simple index fund leaves just about all actively managed alternatives in the dust.

Many index investors, especially first-timers, conclude that they’ve discovered the secret to an endless steak of double-digit returns.

Sadly, this isn’t quite accurate.

Index investing is a smart, effective way to reap the market’s rewards.

Unfortunately, it can’t erase the business cycle or levitate over economic downturns. Inevitably there will come a rough patch, when stocks fall.

If history is any guide, the downturns will sting.

Since the Second World War, the U.S. stock market has endured a dozen bear markets in which the S&P 500 dropped at least 20 per cent.

The FTSE 100 in London has suffered a dozen such declines since 1984.

It’s at times like this that novice index investors tend to fall away. They’re shocked to discover that indexing can, at times, lose money.

Isn’t there a better alternative?

THE MIDDLE-AGED INVESTOR: “I need to find a genius”

Whenever a bear market hits, you will read fawning reports about money managers who warned of troubles ahead and steered clear.

During times like this, it’s tempting to think about ditching an indexing approach and signing up with one of these supposed geniuses.

The problem is that today’s geniuses often turn into tomorrow’s also-rans.

Many of the investors who shone brightest during the financial crisis – people like Crispin Odey in Britain or John Paulson and Bill Ackman in the United States – have been disappointments since.

It’s not that these gentlemen are stupid. It’s simply the nature of the investing game.

Active managers can occasionally beat the market, but their record becomes progressively worse as you extend the period under study.

During 2017, 63 per cent of money managers specializing in large-cap U.S. stocks trailed the index, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices.

Over 15 years, 92 per cent came up short.

You would have had to be unusually lucky to pick one of the few winners.

But people keep trying.

But people keep trying. Unfortunately, the numbers don’t agree.

Most active managers lagged behind the index during the last two bear markets of 2000 and 2008, according to Michael Arone, chief investment strategist at State Street Global Advisors.

To be absolutely fair, active managers do display a modest tendency to look better against index funds during bear markets than they do in more normal times.This phenomenon is known as Dunn’s Law.

It’s frequently cited by advocates for active management as a reason for seeking refuge with a flesh-and-blood money manager.

Unfortunately, that’s a twisting of the facts.

Dunn’s Law was actually invented to explain why the apparent improvement is only a mirage.

The reason is simple: Most active managers have the freedom to venture outside their assigned areas, so they can improve their relative standing by abandoning their core mission.

A European stock manager who diversifies into North American equities during a downturn in the euro zone will appear unusually talented for a while if he’s measured strictly against a European index.

But his apparent skill is actually the result of drifting into hotter markets, not any superior talent at fulfilling his main goal.

Unfortunately, the only way for an investor to take advantage of this tendency is to know in advance exactly which categories will disappoint in the future.

This is rather unlikely.

How unlikely?

Financial author and consultant Larry Swedroe looked at returns for six categories of stocks during the miserable 2008 to 2009 bear market.

He found that, in five of the six categories, active managers failed to beat the index.

THE EXPERIENCED INVESTOR: “I’ll ride out the storms”

With wisdom comes patience.

An indexing strategy will have its ups and downs, but it beats more than 80 per cent of actively managed money over any five-year period or longer, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices.

The trick is getting to that five-year period and well beyond.

At least in my experience, many investors – especially new ones – are shaken by downturns.

They abandon well-planned indexing portfolios in favour of cash or the most recent hot manager.

Then they wind up disappointed when they miss the market’s recovery or their new manager underperforms.

A better strategy is to stick to a well-designed indexed portfolio – but make sure you have a portfolio that is calibrated for whatever level of risk is right for you.

If you don’t want to be hit by a big market drop, tell your adviser so.

He or she can build a portfolio that will be heavier in bonds and other, more stable, assets to help buffer you against the market’s inevitable ups and downs.

You’ll sleep better – and attain the tranquility of an experienced investor that much faster.