Security selection

Another active management technique is security selection, also known as stock picking. This approach involves trying to identify securities that are incorrectly priced by the market, anticipating that the pricing error will eventually rectify itself, resulting in superior performance. Taking the world of Wall Street as an example, active managers classify securities as undervalued, overvalued, or fairly valued. They purchase securities they believe are undervalued, considering them potential "winners," while selling those they deem overvalued, considered potential "losers."

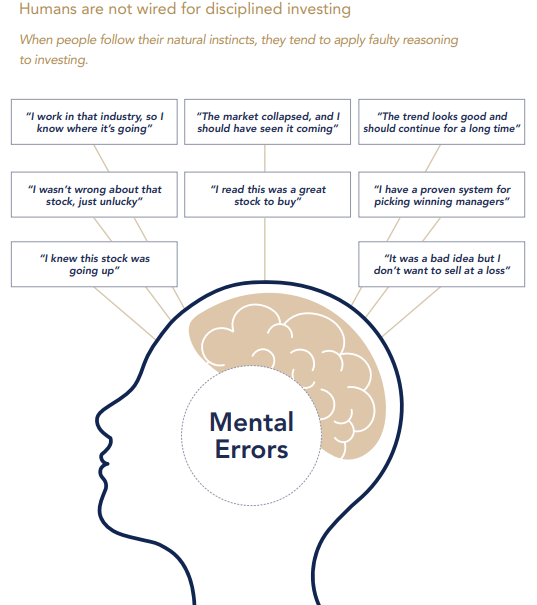

It's important to recognise that every time you buy or sell a security, you are essentially placing a bet. You're trading against the perspectives of numerous market players who may possess more information than you do. In an efficient market, all available information is reflected in the market prices, which means your bet has roughly a 50% chance of outperforming the market (and even lower once costs are factored in).

Once again, the industry of finance and the media have a vested interest in promoting the notion that we can outperform the market by simply being more intelligent and putting in more effort than others. However, with the advent of modern technology, information is easily accessible and swiftly incorporated into securities prices. The functioning of markets relies on the fact that no individual investor can consistently make profits at the expense of others.

The concept that prices accurately incorporate all the knowledge and expectations of investors is referred to as the Efficient Markets Hypothesis in academic circles. This hypothesis was formulated by Professor Eugene Fama of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

The Efficient Markets Hypothesis is sometimes misunderstood as suggesting that market prices are always correct. However, this is not the case. While a well-functioning market may occasionally misprice assets, these errors occur randomly and unpredictably, making it impossible for any investor to consistently outperform others or the overall market.

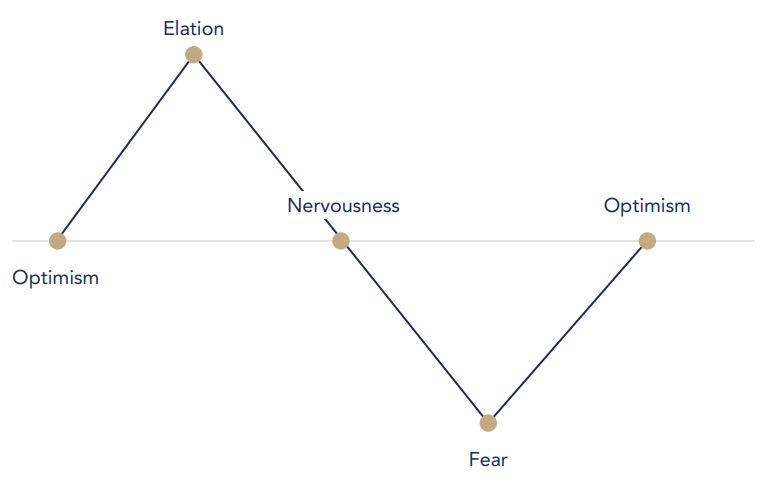

Despite this, many investors still hold the belief that they can beat the market by identifying a smarter, harder-working, and more talented manager—a financial equivalent of Roger Federer or Michael Jordan. It's often easy to identify top performers after the fact, and they are hailed as "geniuses" by the media. However, the challenge lies in identifying tomorrow's top managers before their impressive performance.

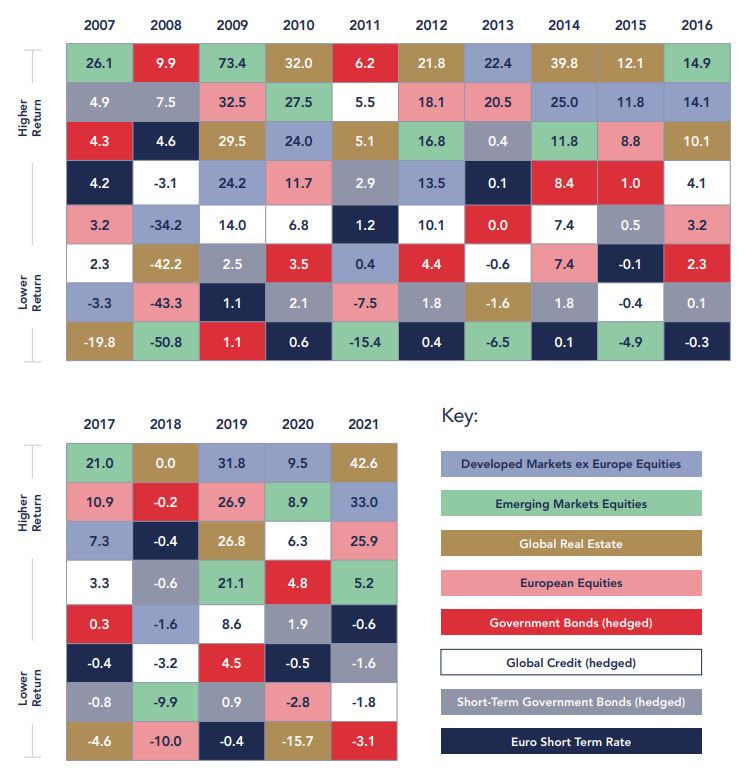

The most common method employed is analysing past performance, (if good past performance indicates good future performance). Financial magazines like Forbes and rating services such as Morningstar capitalise on this data as it drives sales. Mutual fund companies also advertise their best-performing "hot funds" to attract new investors. Despite all these efforts, there's little evidence to suggest that past performance reliably predicts future performance.

Passive investing

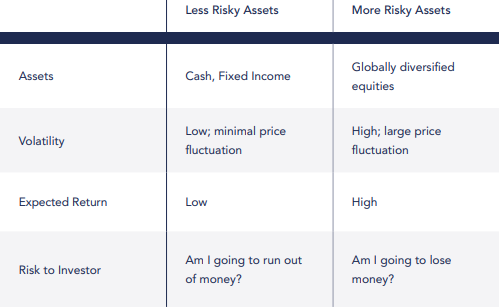

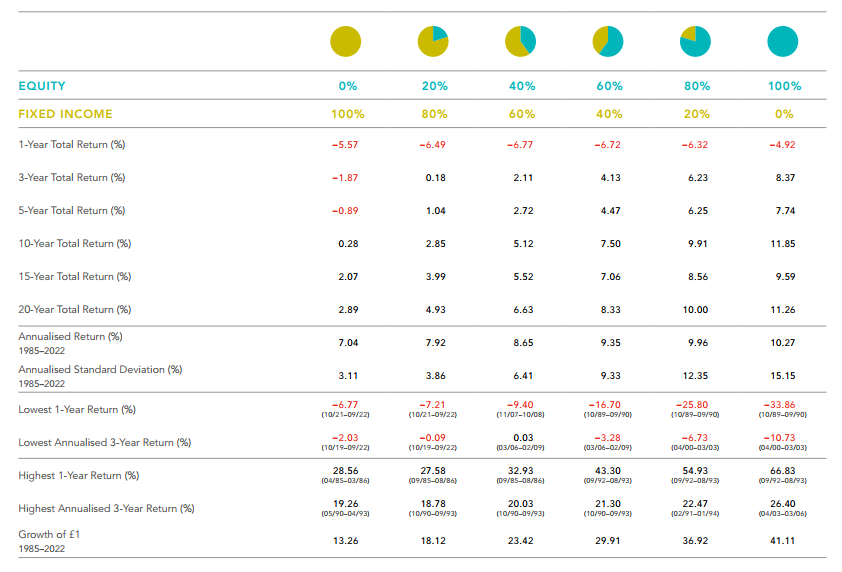

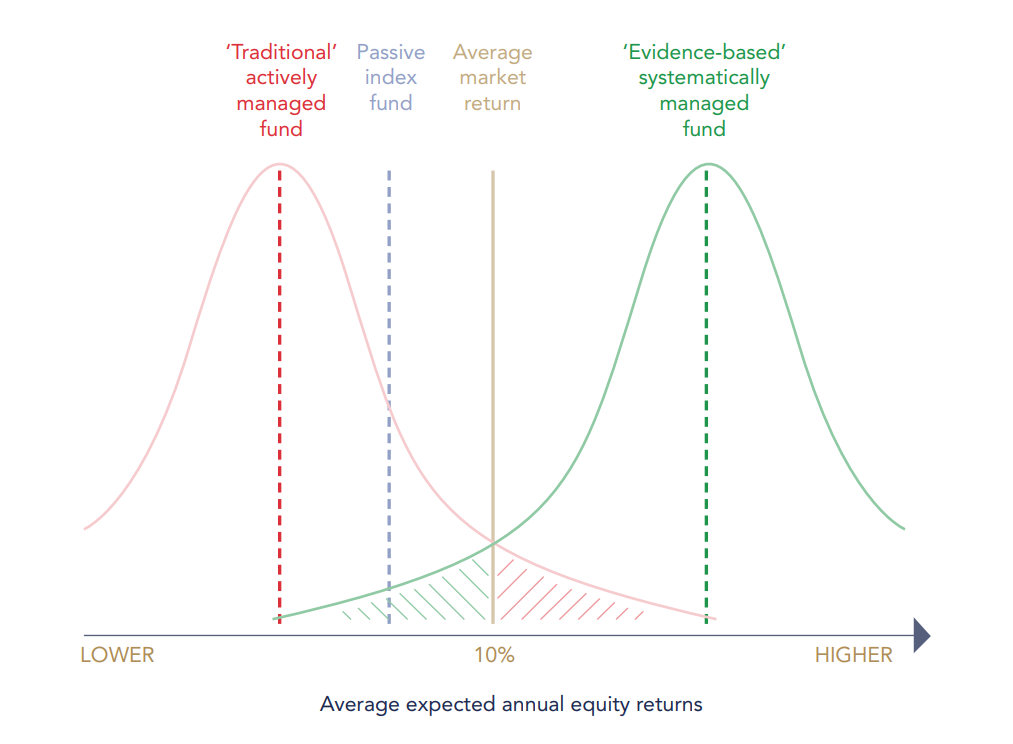

A more rational approach to investing is passive investing, based on the belief that markets are efficient and exceedingly difficult to outperform, especially when considering costs. Passive managers aim to replicate the returns of a specific asset class or market sector by broadly investing in all or a significant portion of the securities within that target category.

The most well-known method of passive investing is indexing, where a manager purchases all the securities in a benchmark index in the same proportions as the index itself. The manager then tracks or replicates the performance of that benchmark, minus any operating costs. The S&P 500, consisting of 500 large-cap U.S. stocks representing approximately 70% of the U.S. stock market's total market capitalisation, is the most popular benchmark index.

Cash drag

Active managers, on the other hand, often hold more cash on hand as they continuously search for the next winning investment opportunity. However, this approach can result in lower returns since the returns on short-term cash investments are typically lower than those of riskier asset classes like equities. Passive managers, by being fully invested, ensure that a larger portion of the invested capital is consistently working for the investor.

Consistency

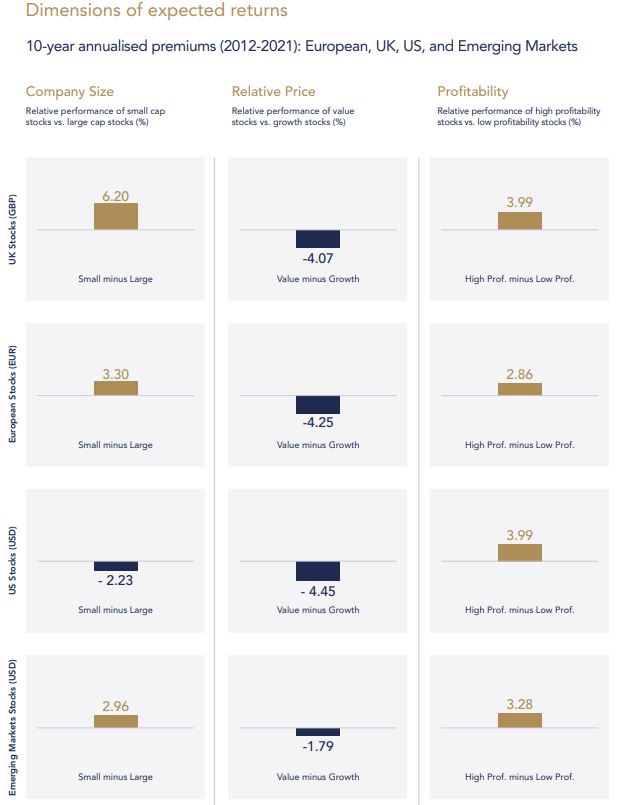

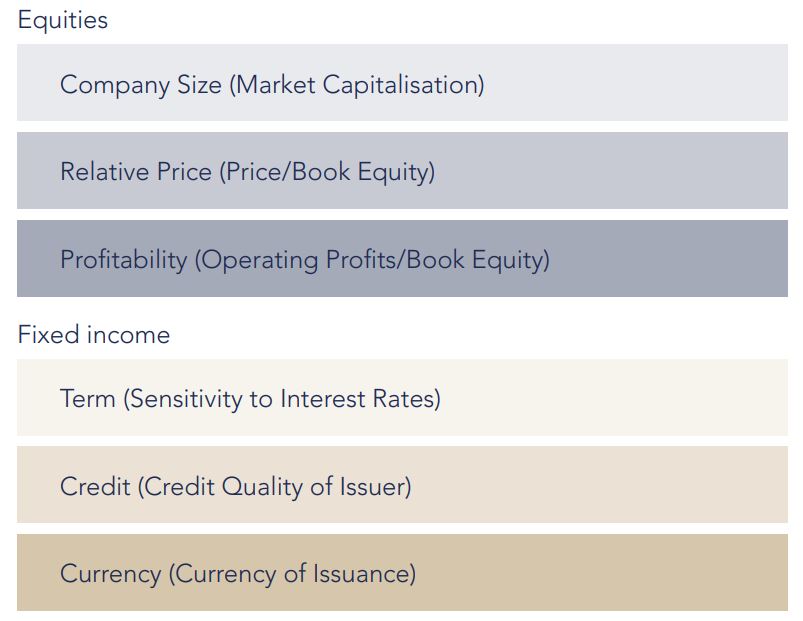

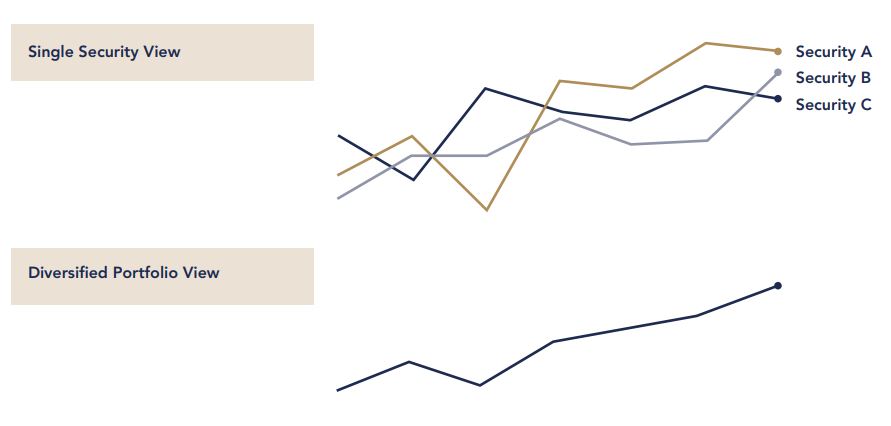

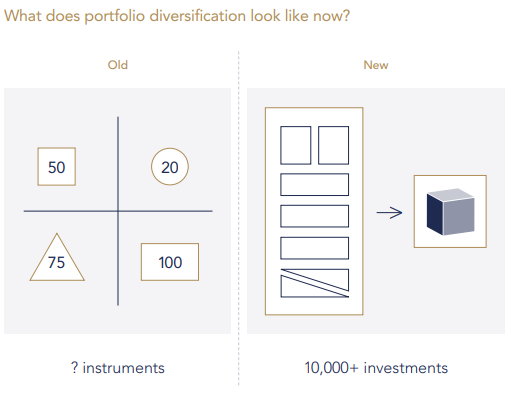

Another advantage of passive investing is the ability to select a group of asset classes that complement each other, acting as efficient building blocks for a portfolio. These building blocks should have minimal overlap in securities (cross-holdings) and possess distinct risk and return profiles.

Active managers may sometimes change their investment style in an attempt to beat their benchmark, for example, by shifting from large-cap value stocks to large-cap growth stocks if they anticipate the latter will perform exceptionally well. However, this "style drift" can create issues, especially when there's already a large-cap growth fund in the portfolio, leading to overlapping risks and reduced diversification. Relying on active managers for portfolio construction relinquishes control over diversification decisions.

Costs matter

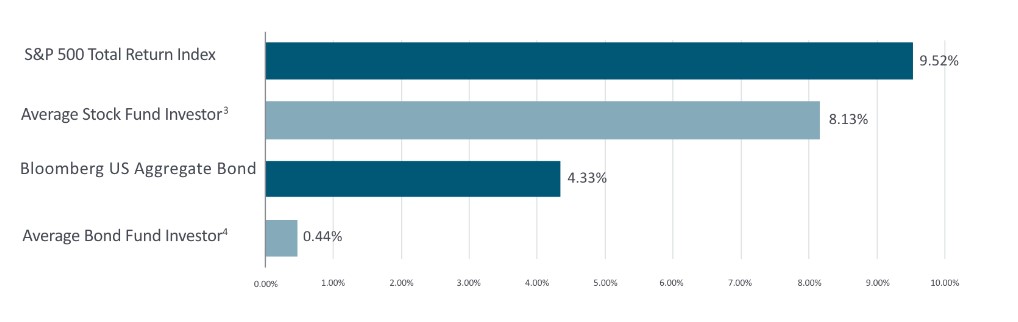

One explanation for the underperformance of active management, as put forth by Nobel Laureate William Sharpe of Stanford University, is that active managers, as a group, will always lag behind passive managers. This is because, collectively, investors cannot earn more than the total market return, and active managers face higher costs due to trading and research expenses. Consequently, the return after costs for active managers as a group is expected to be lower than that of passive managers.

This applies to every asset class, including supposedly less-efficient ones like small-cap and emerging markets. Contrary to conventional wisdom, Sharpe's observation confirms that active managers should collectively underperform by a greater margin in these markets due to their higher costs.

The higher costs associated with active management can be categorized into three areas:

1. Manager expenses

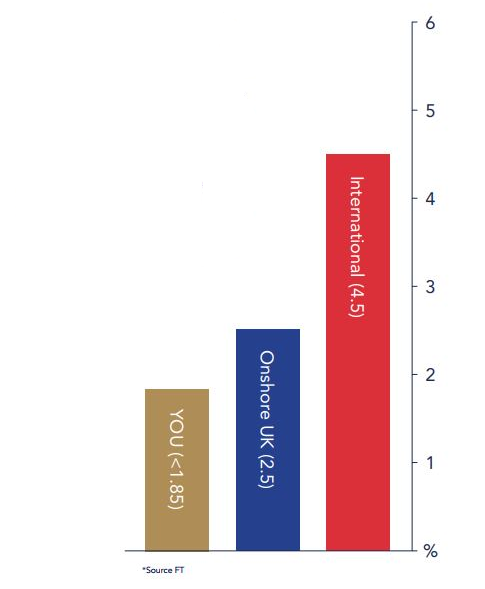

Active managers face greater expenses in employing high-priced research analysts, technicians, and economists who are constantly searching for promising investment opportunities. Additional costs of active management include fund marketing and sales expenses, such as 12b-1 fees and loads, aimed at attracting investments from individuals or persuading Wall Street or City brokers to promote their funds. The difference in expenses between active and passive investment approaches can exceed 1% per year.

2. Increased turnover

Active managers, in their pursuit of superior returns, tend to engage in more frequent and aggressive trading compared to passive managers. This results in higher brokerage commissions, which are passed on to shareholders as reduced returns. Moreover, market-impact costs can rise significantly. When an active manager is motivated to buy or sell, they may have to pay a premium to execute transactions swiftly or in large volumes (like motivated buyers or sellers in real estate). These higher market-impact costs are more common in less liquid market segments like small-cap and emerging markets stocks. Turnover in actively managed funds often surpasses that of index funds by a factor of four or more. The additional trading costs for active management can exceed 1% per year.

3. Greater tax exposure

Active managers' more frequent trading activities result in accelerated capital gains for taxable investors. When a mutual fund sells a security at a profit, investors may receive taxable distributions. For securities held longer than one year, the long-term capital gains rate applies, while short-term capital gains rates apply to securities held for less than a year. The additional taxes resulting from accelerated capital gains generated by active managers may exceed 1% per year.

It's crucial to note that, typically, only manager expenses are disclosed to investors among these three categories. These expenses are usually expressed as a percentage of net asset value in the case of a mutual fund and are referred to as the fund's operating expenses. For actively managed equity funds, the average operating expense ratio is around 1.3% per year. In contrast, passive funds often have significantly lower costs, often below 0.5%.

If the additional costs of active management amount to approximately 2-3 % annually, active managers face a substantial challenge to merely match the performance of a passive alternative like an index fund.