Imagine this: You’ve just booked an airline ticket.

But then you see a cheaper flight online.

The second flight’s departure time is much more convenient – and you could change your ticket without paying an extra fee.

It makes sense to switch flights.

But plenty of people, including Danny Kahneman, might be too afraid to do it.

Michael Lewis profiled Danny in his book, The Undoing Project.

He wrote,

“Danny would resist a change to his airline reservations, even when the change made his life a lot easier, because he imagines the regret he would feel if the change led to some disaster.”

Danny, however, isn’t just some kook.

In 2002, Kahneman won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

He and his partner, the late Amos Tversky, studied how people make decisions.

They found that people often make irrational choices – much as Kahneman might with those airline tickets.

Sometimes it depends on how people frame questions.

For example, medical patients often face the choice of whether or not to undergo surgery.

They’re also notified of the risks.

If they are told, “This surgery carries a 90 percent probability of survival,” most of the patients choose the surgery.

But if the patients are told, “This surgery carries a 10 percent chance of death,” most of the patients elect not to have the surgery.

Yet the odds of survival are the same in both cases.

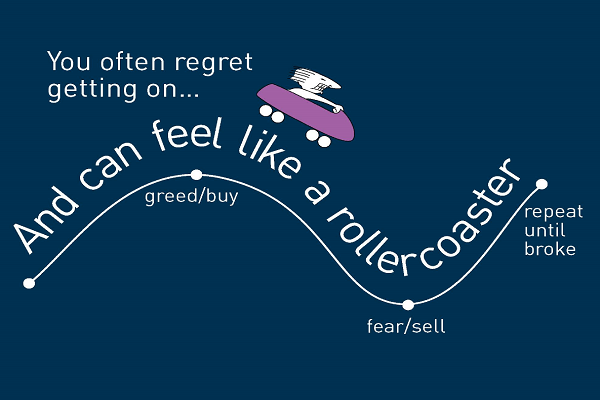

This happens to investors too.

New investors often email me.

They might have accumulated a decent-sized sum in a savings account.

They fear the stock market’s “current unpredictability” (when has it ever been predictable?) and they ask whether they should wait before investing.

They shouldn’t.

Based on probabilities, it’s best to invest as soon as we have the money.

But when the question is reframed, these same investors sometimes see it differently.

Here’s what I ask them:

Assume you have accumulated a seven-figure investment account. Should you sell everything today and re-enter the market at a different time?

Most of the time, these same people say no.

Many of them know that market timing doesn’t work.

By leaving the market for a day, a month or a year, they could miss some of the decade’s biggest gains.

But such incongruent responses are like the medical question.

Investors that keep one million dollars in the market (instead of selling in an attempt to time the market) are making the same decision as someone that invests a cool million in the stock market today.

In other words, choosing to invest a lump sum is exactly the same as choosing not to sell.

And choosing not to buy is exactly the same as choosing to sell it all.

Kahneman and Tversky studied this in their theory of regret.

Explaining their findings, Michael Lewis says,

“The more control you felt you had over the outcome of a gamble, the greater the regret you experienced if the gamble turned out badly.”

Regret, much like Kahneman’s fear of changing an airline ticket, is much deeper if the subject feels they’re more responsible for their mess.

One of Dan Ariely’s theories might also point to something else.

Ariely is the James B. Duke Professor of Psychology and Behavioral Economics at Duke University.

He also co-wrote Dollars And Sense with Jeff Kreisler.

The authors explained that people feel pain when they part with money.

They wrote,

“Studies using neuroimaging and MRIs have showed [sic] that paying indeed stimulates the same brain regions that are involved in processing physical pain… There is a pain we all feel when we give something up.”

That’s why, for some, investing might trigger the same neurological pain.

When coupled with Kahneman and Tversky’s theory of regret, we can see why plenty of people might be reluctant to invest.

Nobody can predict where stocks are headed.

Nobody can convince us not to feel pain when the stock market falls.

But the stock market rises more often than it drops.

Over your lifetime, your children’s lifetime and your grandchildren’s lifetime, stocks will keep hitting new all-time highs.

That’s why new investors should invest as soon as they have the money.

They should build diversified portfolios of low-cost index funds.

Each time they get paid, they should add more money – and they shouldn’t worry when the market falls.

Theologian, Reinhold Niebuhr, didn’t write his famous prayer as an investment guide.

But it’s timeless stock market wisdom:

God, grant me the serenity

to accept the things I cannot change [like short-term stock market movements].

Courage to change the things I can [like diversification and investment costs].

And wisdom to know the difference.

Perhaps these words should be printed on every brokerage statement.

Many thanks to Andrew Hallam, author of the bestseller, Millionaire Teacher and Millionaire Expat: How To Build Wealth Living Overseas, for letting us repeat this blog on The Scientific Investor. The original was published on AssetBuilder.com in April 2018.