When Ronald Read died at age 92 in 2014, his friends and family were surprised to discover he had been hiding a secret.

The retired janitor and gas station attendant, who lived in rural Vermont nearly all his life, had quietly accumulated a fortune of $8 million despite never earning more than a modest income.

At exactly the same time, not that far away from where Read grew rich, far better paid people were apparently scrambling to make ends meet.

“It’s really not that unusual to find Wall Street bankers who are close to declaring bankruptcy,”

Gary Goldstein, co-founder of executive search firm Whitney Partners, told a journalist in 2013.

“Some people are really struggling.”

There are at least two lessons to take away from these contrasting cases.

One is that you don’t need a big salary or an insider’s knowledge of financial markets to wind up wealthy.

From all accounts, Read simply bought stocks in companies he knew and held them patiently for decades.

The other important lesson is that what really matters is developing a habit of saving money.

Read succeeded because he lived below his means – something Wall Street bankers are apparently rather dismal at doing.

These are lessons we should all keep in mind.

If you’re looking for a financial adviser, you will hear lots of pitches promoting the virtues of exotic investing strategies.

You will very rarely hear advisers talk about the true secret of building wealth, which amounts to persistently saving money and sticking to a sensible investing plan.

Proof that this approach works comes from “The Millionaire Next Door”, a landmark academic study of wealthy Americans done in the mid-1990s.

The researchers discovered that the link between income and net worth isn’t nearly as strong as you think. (Ronald Read could have told them that!)

People who make lots of money often spend it on clothes, cars and houses.

Those who make less but are saving regularly wind up with far more money in the end.

So why aren’t more of us big savers?

It probably has something to do with our natural urge to impress others with our expensive possessions.

Unfortunately, keeping up with the Joneses leads to a never-ending treadmill of spending more and more for diminishing amounts of satisfaction.

Rather than striving to project a facade of affluence, we may want to take a lesson from some of the world’s most prominent billionaires.

A surprising number are anything but conspicuous consumers:

- Warren Buffett, the multi-billionaire investor, still lives in the house he bought in 1958 for $31,500.

- Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, drives a Volkswagen GTI hatchback he bought in 2014 for about $30,000

- Ingvar Kamprad, the recently deceased founder of Ikea, ate in the Ikea cafeteria and drove the same car for 20 years, despite being the eighth richest person in the world.

Billionaires aside, a regular habit of saving money can even make you more attractive to potential partners, according to an academic study of what people find alluring in potential mates.

But before we get to that fascinating piece of research, let’s examine some key issues around saving.

How to save

Any personal finance expert will tell you that the most painless way to put away money is to pay yourself first.

It’s a classic piece of savings wisdom, because it works.

Paying yourself first means you set your savings target and have that amount automatically deducted from your paycheque before you even see the money.

Ideally, you set things up so your savings are then whisked into a pre-determined investment program.

This approach pays off in several ways.

First, you’re not exposed to temptation the way you would be if you had the money in your wallet.

Second, you don’t have to draw up a budget and rely on your ability to stick to it – you simply live on what’s left over after your savings are deducted.

Third, you reduce the perceived pain of saving, since you don’t see the money before it’s invested.

How much to save

The short answer is 20 per cent of your gross salary.

Yes, ouch: I can hear your pain from here.

But the numbers are beyond dispute.

Saving 20 per cent of your salary every year, and investing it in a way that produces historically typical results, will let you accumulate 10 to 12 times your salary in savings over the course of a 30- to 35-year career.

Assuming the past is any guide, that amount of savings will then generate a retirement income equal to roughly half of your working income.

Combine that with any employer pensions or government stipends, and you will have ensured yourself a comfortable retirement.

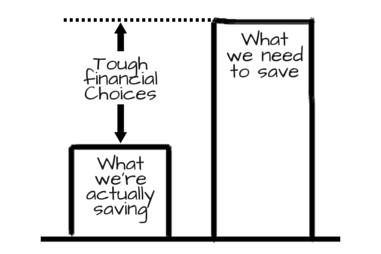

What happens if you can’t save 20 per cent of your income right now?

It’s still important to save as much as you can.

After all, what you don’t put away today, you will have to make up tomorrow.

All things being equal, however, starting early puts you in a much better position.

You gain an advantage because of the magical effect of compounding – that is, the gains you achieve by reinvesting the money you make on your investments.

To see the power of compounding in practice, consider someone who invested $100,000 in the Vanguard 500 Index Fund on February 28, 1997.

If she didn’t reinvest her gains, her savings would have grown to $295,480 by February 28, 2017.

However, if she put all her dividends, interest or capital gains back into the fund, her nest egg would be $426,500 – more than a third greater than the non-compounder.

How to save happily

Peter Adeney, who writes the Mr. Money Mustache website, credits his strong savings habit with allowing him and his wife to retire at age 30.

His simple-living style may not appeal to everyone, but one of his insights should.

It’s about how to be happy while saving money.

Adeney says the secret is learning how to use hedonic adaptation to your advantage.

Despite its formidable-sounding name, hedonic adaptation refers to a very simple concept: It’s our tendency to experience short bursts of happiness when we acquire a new possession, but quickly revert to our baseline level of happiness, usually within a couple of weeks.

Once we’re aware of this tendency, Adeney says, we can use it to our advantage by parcelling out our discretionary spending in small doses and spacing those luxuries over longer intervals.

Rather than renovating our entire house all at once, we can do it in stages, enjoying each incremental improvement before looking forward to the next.

Similarly, we can upgrade our wardrobe one item at a time, instead of buying everything in one massive spending binge.

By taking things slow, we can give ourselves time to savour each tiny step forward.

How to think about savings

Picture your savings as a big life preserver.

It provides a buffer against job loss or unexpected major expenses.

Ideally, you should have some money set aside outside of your investments, which you can draw on in case of an emergency.

But even if you have to temporarily withdraw money from your investments, you are still further ahead than you would be if you had to borrow money and pay off bank loans or credit card debts.

You can also picture your savings as a shock absorber.

By arranging to make regular, fixed contributions to your investment account, you benefit from what’s known as dollar-cost averaging.

This means you automatically buy more shares of a fund when the price is low, and fewer when the price is high.

Over the long term, this reduces your average cost per share – without any effort on your part to time the market.

Finally, you can think of your savings as a relationship enhancer.

A 2017 paper by researchers at the University of Michigan found that people consistently rated savers as more enticing romantic partners than non-savers.

The study, called “A Penny Saved is a Partner Earned”, acknowledged that this attraction might partly be a desire for partners with greater financial resources.

Mostly, though, the appeal seems to reflect the tendency of a strong savings habit to signal greater self-control in all areas of life.

Talk about big payoffs: A strong savings habit isn’t just financially wise.

It’s sexy too.

Maybe it’s time to start flaunting your ability to put away money.